Welcome to Feedback Fundamentals. In this series, we’ll be getting back to the basics and highlighting what it means to “close the loop.” Whether you’re well versed in the jargon or new to the feedback community, this series will introduce you to ideas, frameworks, tools and approaches that we believe are essential for a strong feedback practice. Feedback Fundamentals is all about building a strong foundation and realizing a vision of listening to the people you seek to serve.

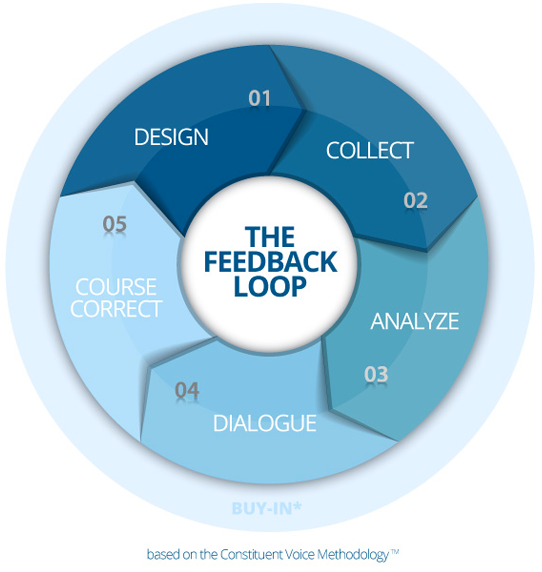

We’ve defined what we think a closed feedback loop is in six discrete steps. We’ll be exploring one step of the loop in each article, from Buy-in through Course Correct. But before we get into the steps of the loop, we want to take a small step (sorry) back and talk a little bit about how we got here. At FBL, we have an underlying thesis about feedback: that it is the right, smart, and feasible thing to do. We think these three components form the pillars of the argument for feedback. There’s something for everyone in this argument: it speaks to the heart, it speaks to the head, and it speaks to the wallet.

RIGHT

The right component seeks to articulate the ethical and moral imperative to treat stakeholders who have traditionally been marginalized, infantilized, disenfranchised, or otherwise written off as inconsequential in aid and development scenarios as full and equal partners. It weighs their opinions and perspectives equally, if not more, than traditionally “acceptable” forms of evidence in design making processes. That is a long-winded way of saying that we have to stop treating “beneficiaries” as if they don’t have a right to an opinion about the policies and programs imposed on them. This component resonates most with those who advocate that constituent voice is the most ethical way to conduct aid and philanthropic business – and that group of people may be growing.

SMART

The smart component is the one we hear the most about, is often the most contested and, for many, is the argument needed to secure funding for feedback programs. This component seeks to establish the relationship between integrating feedback and getting better outcomes. We’re not the only ones who have done a lot of thinking in this area: from deciding when and how feedback should be used as evidence, to redefining how we think of outcomes in light of better evidence, feedback is being heralded as a critical ingredient for improved results in health, education, humanitarian response, disaster relief, philanthropy, and many other sectors.

FBL explored this component in-depth at our May 2016 Smart Summit. We assembled the available evidence on the connection between feedback and improved outcomes and invited the community to share and debate it. As the aid, development, philanthropic, and governance sectors increasingly embrace constituent feedback, further research will enable these groups to better measure and document its use and effect.

FEASIBLE

Even if you believe that feedback is the right thing to do and the smart thing to do, if you can’t make it happen, then you won’t close your loop. Feasibility is arguably the number one challenge for most people to successfully design and implement a closed feedback loop. Costs, technology, stakeholder complications, lack of buy-in, or simply feeling overwhelmed are just a few barriers that decrease a perception of feedbacks’ feasibility . At FBL, we focus our energy on learning how to make closing the loop feel more possible and packaging that learning in accessible ways for you, our community. We built a Quiz to help you identify your strengths and areas for improvement, and developed an accompanying Toolkit to connect you with resources. We try to integrate the use of feedback into everything we do, so we make sure that we’re walking the talk and can speak from a place of experience. We collect your insights in our Three Things Thursday blog series, where you reflect on your work and offer three bits of wisdom on what enabled you to close your feedback loop. And you have shared some incredible tips and tricks:

- Focus on incremental change when trying to shift policy

- Simplify citizen engagement documents to ensure greater constituent participation

- Recognize feedback in all of its forms to ensure that you’re squeezing the most out of your citizen engagement mechanisms

- Build course correction into your timeline so you don’t have an excuse for not doing it

- Give your frontline staff lots of autonomy to frame questions since they’re closest to the people you’re trying to serve

- Thank people for reporting in order to start building a trusting and respectful mutually beneficial relationship

Getting, understanding, and really using feedback is hard, there’s no doubt about it. But with advances in technology and political, social, and economic environments that are increasingly friendly to feedback loops, it’s becoming more and more feasible.

Right, Smart, Feasible. We think these are the pillars of the feedback argument, and we’re building our work, services, and products around this hypothesis. What do you think? Are these the primary components when you argue in favor of feedback loops? Leave your comments below or with us on Twitter @FeedbackLabs.

Next up: We’ll be tackling the first step of the feedback loop— getting buy-in.