A few weeks ago we asked, “Do we bias the feedback we get?” The emphasis was on ensuring that respondents give answers that are unbiased and therefore “true”. It turns out that responses vary depending on how you frame the decision and the context in which the decision is made.

But could our own listening is biased too?

In other words, as projects collect constituent (beneficiary) feedback, there’s a risk that the project implementers or funders will misunderstand the feedback, as they try to make sense of it. Listening is different from hearing in that listening requires us to make sense of the information received; listening requires some act of interpretation.

It’s common for someone to say something that is misinterpreted by another. The way things are interpreted often depends on how the utterance fits within the listener’s existing schema of the world.

Take for example the case of feedback in the workplace. Increasingly, workplaces are improving in their openness to giving and receiving feedback across hierarchical levels. But the system is far from perfect. One issue in particular that has received much media attention lately has to do with gender bias and the role of interpretation in communication.

Do our gender biases affect how we listen to what others say? Do our expectations for the “right” behavior depend on certain gender norms?

The Wall Street Journal addressed the subject in an article, Gender Bias at Work Turns Up in Feedback. The article summarizes research from Stanford University’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research. One point is that women received 2.5 times the amount of feedback men did about aggressive communication styles, with phrases such as “your speaking style is off-putting”.

It’s doubtful that what women said was really 2.5 times more off-putting. It’s more likely, and supported by mounting research, that communication was interpreted differently because of the gender of the speaker.

So what does this have to do with collecting constituent feedback?

Unless we’re well versed in the semiotics of a person and a place, a lot of misinterpretation could happen.

As funders and project implementers embarking on closing the loop with constituent feedback, how can we better interpret what we hear? How can we un-bias our listening or learn to read between the lines?

The feedback we get, especially that which is free form (and thus arguably the most useful), will inevitably be laden with associations that we —the surveyors—give it.

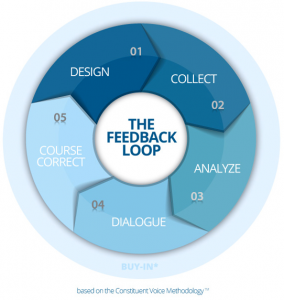

It’s incumbent upon us to fully close the loop by making sure we have open dialogue with constituents about the feedback, after it’s been collected and analyzed. This open dialogue can help shake-up our own assumptions and disentangle the meaning of what people say.