In this piece, we try to understand why feedback means different things for different people in aid and philanthropy—and how that’s okay.

The international development industry spends a lot of time looking forward. So much so, in fact, that there isn’t much time for looking back. Incentives are set-up for people to “disrupt”, “innovate”, or a new-fangled favorite—“ideate.”

It’s often more exciting to look forward than back. And it helps our egos to feel like pioneers. But history has a lot to teach us. Everything has an origins story and so it is with feedback.

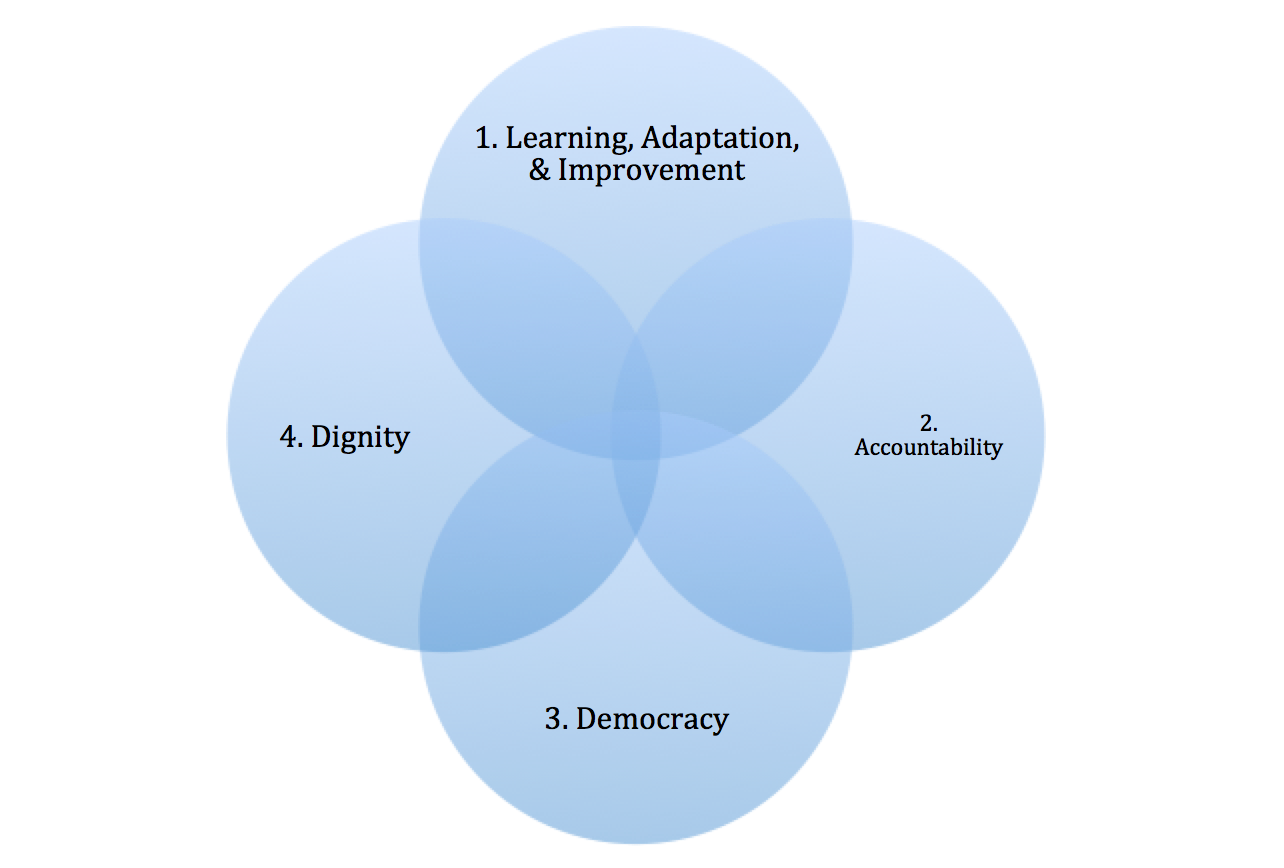

When we talk about feedback, what do we mean? Is it new? Is it innovative? Are we heralding a new world order? Implicitly, we coalesce around a vague meaning even though independently, we all harbor slightly different definitions. Even in a group of 70 people from the aid and philanthropy sectors, definitions can be wide-ranging. At the 2015 Feedback Summit, participants were asked to independently submit their definitions of feedback before the event, when they registered. From this group, several dominant (non-mutually exclusive) themes emerged:

The differences spring from the fact that feedback, as a movement, involves many actors, each with a unique set of interests. These interests, in turn, are shaped by particular historical legacies. By understanding our colleagues’ histories, we move forward together better. In the following, we briefly suggest that several historical trends, in both the private and public sectors, may have resulted in people defining feedback the way they do today. These historical trends are:

- participatory and community development

- social accountability

- customer satisfaction

- organizational learning

a) Participatory and community development

Participatory and community development involve efforts to induce community engagement in service delivery. Often these efforts are created to manage development resources without relying on formally constituted local governments. [1]

Participatory and community development has a long history. The first wave began in the post-colonial era (1950s and 1960s) very much as development was itself beginning to professionalize as an industry. Mansuri and Rao explain in Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? that by 1959, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) had spent more than $50 million in community development projects in 30 countries. During this time, these projects were used as a foreign policy tool to promote democratic alternatives to communism.

The popularity of participatory and community development waned briefly in mainstream aid and philanthropy but came back in new forms including Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation, among others. This time around, though, the objective was slightly different. Rather than focusing on democracy, it was now rooted in more moral cosmopolitan concepts related to human rights, human dignity, and social justice. The thinking of Pablo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), is commonly cited as foundational to PAR and the later work of the popular participatory development scholar, Robert Chambers.

This history of participatory and community development helps explain why some within the aid and philanthropy communities approach feedback from the perspectives of democratic liberalism (theme #3)—grounded in rights to liberty and equality— and dignity (theme #4). This activist camp is also more likely to see feedback as “agency” or “empowerment”— something deeply procured and integrated from the very beginning of a project and not just as a rapid response to a project’s existing activities.

This history of participatory and community development helps explain why some within the aid and philanthropy communities approach feedback from the perspectives of democratic liberalism (theme #3)—grounded in rights to liberty and equality— and dignity (theme #4). This activist camp is also more likely to see feedback as “agency” or “empowerment”— something deeply procured and integrated from the very beginning of a project and not just as a rapid response to a project’s existing activities.

b) Social Accountability

While not wholly distinct from the participatory and community development work before it, social accountability’s focus is on building demand-side accountability from citizens within more formal systems of government. A key document for the social accountability movement is the World Bank’s 2004 World Development Report: Making Services Work for Poor People.

According to a subsequent 2006 World Bank Social Accountability Sourcebook, “social accountability is about affirming and operationalizing direct accountability relationships between citizens and the state. Social accountability refers to the broad range of actions and mechanisms beyond voting that citizens can use to hold the state to account, as well as actions on the part of government, civil society, media and other societal actors that promote or facilitate these efforts.”

Examples of tools for social accountability include civic engagement tools like community scorecards, participatory budgeting, deliberative polling, and public hearings.

Social accountability also tends to focus on issues of governance and transparency. Activities around open government and open data typically come from this historical legacy. They use words like “citizen” (much more than constituent, beneficiary, client, or stakeholder), “voice”, and “openness”. This framing of social accountability helps explain why some in aid and philanthropy approach feedback from the perspectives of accountability (theme #2) and with the principles of democratic governance (theme #3).

Social accountability also tends to focus on issues of governance and transparency. Activities around open government and open data typically come from this historical legacy. They use words like “citizen” (much more than constituent, beneficiary, client, or stakeholder), “voice”, and “openness”. This framing of social accountability helps explain why some in aid and philanthropy approach feedback from the perspectives of accountability (theme #2) and with the principles of democratic governance (theme #3).

c) Customer Satisfaction

Measurement of customer satisfaction began to rise rapidly in the 1980s. The metric is seen as important to business for the following reasons: 1) it is a leading indicator of loyalty; 2) it is a point of differentiation from other businesses; 3) high customer satisfaction helps spread positive reputation by word-of-mouth; 4) it is cheaper to retain customers than obtain new ones; 5) it increases customer lifetime value; and 6) it reduces customer churn [2].

In 2003, the Net Promoter Score (NPS)—which later became the Net Promoter System—was introduced as a specific metric of customer loyalty and is used today by many companies to monitor company performance. The system behind the NPS asks two questions: “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely are you to recommend our company/product/service to your friends and colleagues?” and “Why?” By assessing customer feedback, companies are able to flexibly respond, adapt, and improve their offering for the marketplace while strengthening customer relationships. In one study, companies with the highest customer loyalty typically grew revenues at more than twice the rate of their competitors. [3]

The influence of the private commercial sector in aid and philanthropy has led some people to approach feedback as necessary for product or service learning, adaptation, and improvement (theme #1). With aid and philanthropy lacking a responsive price indicator to determine the value proposition of products and services, feedback is seen as a potential proxy for understanding whether constituents actually want what is being given.

d) Organizational learning

If you work in a big organization, it’s likely someone is doing something called “knowledge management” to help organizational learning. Organizational learning, as a focused study, began in the late 1970s. It refers to the process of creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge within an organization.

Some people in this field argue, though, that knowledge is often not a tangible thing that is easily captured or consumed. These people focus, instead, on tacit— or experiential— knowledge. Tacit knowledge is intangible, complex, and difficult to separate both from the person who created it and from the context in which it was created. To develop tacit knowledge requires practice—trying, erring, getting feedback, and course-correcting.

Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, gives the example of learning to walk or ride a bike: we learn through multiple attempts and bodily feedback— each time our bodies, our muscles, our sense of balance react to this feedback by adjusting to succeed.

In this way, the field of organizational learning also informs how some people within aid and philanthropy think of feedback as necessary also for learning, adaptation, and improvement (theme #1).

Its historical legacy appears at aid agencies and nonprofits that acknowledge the tremendous complexity of their work and are therefore trying out feedback for “adaptive management”. USAID explains that, “Adaptive management can increase Missions’ ability to respond quickly to both changing environments and in the event that the original framing proves inadequate, inaccurate, incomplete, or unrealistic.” [4] Moreover, monitoring and evaluation (M&E) within aid and philanthropy has increasing taken on the letter “L”—for learning. We see, for example, whole departments changing to MEL, MEAL, or MERL.

Mutual reinforcement across our differences

What’s powerful is that none of the definitions need to be mutually exclusive. Feedback for learning (theme #1) and feedback for accountability (theme #2) are actually two sides of the same coin that have the same ultimate objective of greater social impact. Democracy (theme #3) and dignity (theme #4), while not the same, align if we believe that democracy, for many people, is a means to achieve dignity.

Admittedly, definitional diversity can get messy when the learning camp talks to the dignity camp. The dignity camp often values “perceptual” feedback that is subjective and speaks to an individual’s or communities’ opinions, values, and feelings. The learning camp, on the other hand, often values “non-perceptual” feedback: objective, more generally defined data that is collected from a person versus actively voiced by a person.

Examples of perceptual feedback on a service might include the following statements: “I benefited a lot from this service” or “I enjoyed this service.” In comparison, an example of non-perceptual feedback may be a software application that tracks a person’s behavior (i.e. the number of footsteps in a day) and relays it to the person or her physician.

It is important to note that even this seemingly large difference may not be so big. Perceptual feedback is data that, like non-perceptual data, can help organizations learn, adapt, and improve their products or services. The field of customer satisfaction is, in fact, about helping organizations learn, adapt, and improve. At the same time, customer satisfaction depends on largely perceptual feedback—data that is based on subjective customer opinions, values, and feelings.

So how do we move forward with all these definitions? The feedback terrain is, indeed, a crowded space.

Our recommendation is to embrace the diversity. Feedback does not need to be only one thing for everyone. Sure, there will be some disagreement and natural fragmentation. But more often than not, there will be complementarities and areas for mutual reinforcement.

In the very spirit of feedback, the movement is open to everyone.

[1] Mansuri and Rao (2013). Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? The World Bank.

[2] http://blog.clientheartbeat.com/why-customer-satisfaction-is-important/

[3] Reichheld and Markey (2011). The Ultimate Question 2.0, Harvard Business Review Press

[4] USAID, “Adaptative Management,” USAID Learning Lab website. Accessed online at https://usaidlearninglab.org/learning-guide/adaptive-management on January 20, 2016.