September 6, 2015

It matters how we choose our words. Today, the word “beneficiary” is being replaced with citizen, client, consumer, stakeholder, and constituent. What are the pros and cons of each?

It is 2015. We still use the word “beneficiary”.

I use “beneficiary” for lack of a better word. I use quotations to show that I’m not wholly comfortable with the vocabulary.

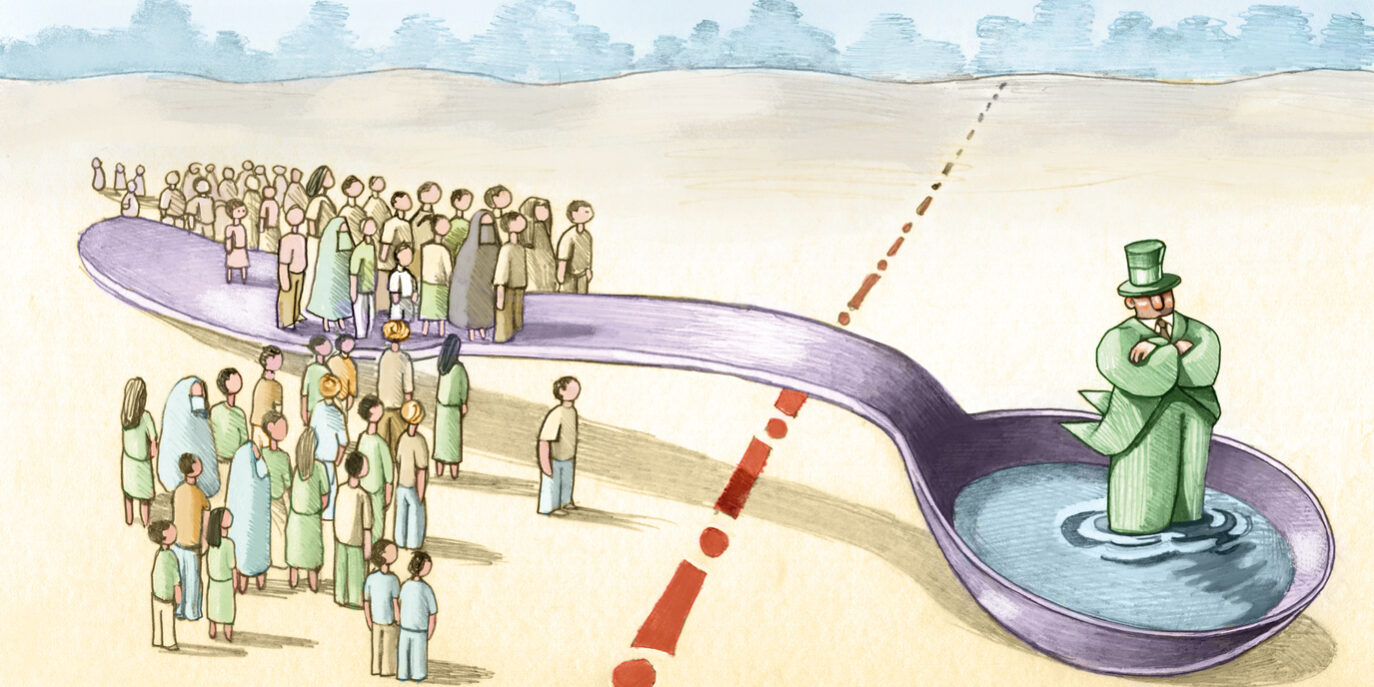

In the act of naming, subjects are born. In the act of reiterating the name, power dynamics, inequalities, and structural violence are reinforced. And so it is with the word “beneficiary”.

To be a beneficiary implies a relational weakness to the benefactor. It also implies that what she receives is bene or good. Descriptively, “beneficiary” partially works: in the current system of aid and philanthropy beneficiaries are, in fact, largely disempowered; at the same time, however, it’s questionable that what they’re receiving is all that bene.

A movement that is trying to radically change a broken system of aid and philanthropy needs a vocabulary that is less descriptive and more normative: what should we be calling “beneficiaries”?

Normatively, we need a word that empowers “beneficiaries”. But what are alternatives that could also be accurate descriptively? The following is some of my early, abbreviated thinking.

CITIZEN

Some organizations use the word “citizen” in lieu of “beneficiary”. “Citizen” projects the notion of a social contract between those who govern and those who are governed. It sheds light on the fact that there is no real system of governance that binds the benefactor and beneficiary in a way that creates a political community and confers both rights and responsibilities to its community members.

And while I like the ethos of “citizen”, I stutter with the word.

-

“Citizen” is for sovereign nation-states

Since the 17th century, “citizen” has been largely a legal term. Sovereign nation-states have citizens. Funders like the Gates Foundation and the Asian Development Bank do not. NGO implementers also do not.

-

Some “beneficiaries” are not actually citizens

As a legal term, there are many “beneficiaries” who are not actually citizens of nation-states: refugees, undocumented migrants, and the 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States, to name a few. Surely, their voices need to be heard by too.

-

Many citizens live under totalitarian regimes

Do we implicitly assume a liberal democracy when we say “citizen”? Many of us come with biases of a republican model of civic self-rule. But there are many citizens that don’t come from this historical trajectory.

How does the World Bank plan to mainstream “citizen engagement” in its operations in countries that are less democratic? How would a NGO working on incarceration and recidivism in the United States work with the 5.8 million people who cannot vote due to a felony conviction?

CLIENT

“Client” stands in stark contrast to “citizen”. While citizenship implies rights and obligations within a political community, clientship is what fills the vacuum with the rollback of the state, when the state is not able to fulfill its obligations to its citizens. Clientship is the result of the projectification of service delivery across different donor-funded initiatives. The “client” in clientship, in this way, is perhaps accurately descriptive of what the “beneficiary” is.

There is a good piece, Therapeutic Clientship: Belonging in Uganda’s Projectified Landscape of AIDS Care (Whyte, Whyte, Meinert, Twebaze 2013) that strongly influences my thinking on the word “client”. The authors write:

“‘Clientship’ is a productive double entendre when applied to the field of [antiretroviral therapy] ART in Uganda. The patients receiving ARVs through AIDS clinics are clients in the ‘user-of-services’ sense; that is, they are people utilizing the professional expertise provided to them by rational bureaucratic organizations. They are also dependent for their lives on access to ARVs dispensed by donor-funded projects, and they are drawn into exchange relationships with projects and people controlling access to those vital resources. In the classic pattern of patron-client relations, they tend to personalize their interactions with health workers and other project personnel.”

The “user-of services” or “service-mindedness” sense of “client” seems benign enough and I’ve even resigned myself to its neoliberal tinge.

But what really bothers me is the patron-client hierarchy in clientship.

-

A client is “serviced” but she can also be dependent on her patron and systems of patronage

The inequality that clientship perpetuates is not that different from the benefactor-beneficiary hierarchy that we see in aid and philanthropy today. Arguably, it’s even worse: in a benefactor-beneficiary hierarchy, the benefactor gives and the beneficiary receives. On the other hand, in a patron-client hierarchy, the benefactor gives but the “gift” is conditional upon somewhat intangible goods (i.e. loyalty, etc). There is an exchange, a transaction.

It means that “clients” have to build patron-client relationships and how one builds those relationships is dependent on existing social, political, and financial capital. The poorest of the poor (often the targeted “beneficiaries”) are those with the least capital and may not have access to the very projects that would make them “clients”. As the authors explain, this kind of clientship can be exacerbated when mapped onto the existing clientelistic, neopatrimonial relationships that define many developing countries in which aid and philanthropy operate.

-

A client is sometimes not the ultimate “beneficiary”

The World Bank, among other multilateral lending organizations, refers to the countries to which it lends or grants as clients. The obvious problem is that the persons for whom the aid is ultimately intended are not mentioned, and certainly not empowered.

One interesting article talks about inverting “client” from the perspective of the private consulting companies—those that take multi-million dollar contracts from major donors like USAID. These companies typically refer to the donor agencies as “clients”. The article suggests repurposing the word, instead, for “beneficiaries” in a new type of “client-driven development”. While I like this idea, unfortunately, its merits do not overcome the other problems I encounter with “client” in points above.

CONSUMER

No one in the aid and philanthropy world has actually put forth “consumer” as an alternative to the word “beneficiary”. However, there are various efforts to begin treating them like consumers in a private commercial market. Namely, developing a practice of “beneficiary satisfaction” that would be analogous to customer satisfaction.

I generally like the spirit of “beneficiary satisfaction”. It suggests that the beneficiaries in aid and philanthropy are powerful in relation to their suppliers.

But this mental model is problematic as well:

-

Supply does not feel an existential threat from demand

As a consumer in a private commercial market, you have power because you can move your spending elsewhere. Beneficiaries don’t exist in this kind of market; they don’t have this kind of power to influence supply. Companies care about consumer feedback and public customer satisfaction ratings because if they don’t listen to it, it means they’ll lose customers, market share, profits, and eventually go out of business.

Government agencies (within liberal democracies that feel accountable to their citizens) might be able to leverage this model of customer satisfaction. This is perhaps why the US government recently decided to partner with Yelp as a rating platform for its agencies. But critics are quick to point out that while these platforms allow people to be heard, the real problem is how you get agencies to listen and act. The White House online petition site, We the People, has been criticized for not responding to petitions even after they achieved the 100,000-signature requirement.

If even government agencies within democratic regimes don’t feel an existential threat from “citizen satisfaction” ratings, let’s be honest: will there really be an existential threat to the funders in aid and philanthropy?

The avenue I find most exciting is if funders in aid and philanthropy decide to require “beneficiary satisfaction” of their grantees. There would be at least an existential threat to project implementers who depend on grant funding.

-

Customer satisfaction but who is your customer?

Being a consumer frequently implies being an individual private consumer. In aid and philanthropy, goods and services are rarely that individual and private. On one hand you have public goods (non-excludable, non-rivalrous). On the other hand, you have private goods that can have externalities (knock-on effects) for others in the community.

So if we’re thinking about importing the individualized “customer satisfaction” model, we ought to carefully ask ourselves “customer satisfaction for whom?”

The World Bank might invest in flood prevention infrastructure that helps some customers stay above water but also displaces others. The International Finance Corporation might invest in a coal-fueled power plant that helps some customers get energy but also destroys the livelihoods of fishermen.

STAKEHOLDER

“Stakeholder” implies a party that has an interest in an enterprise or project. A corporate enterprise might have multiple stakeholders with different, even competing interests (i.e. shareholders and employees are both types of stakeholders).

-

Everyone’s a stakeholder

“Stakeholder” seems to work. But that’s mainly because it’s far too general of a term and doesn’t say a whole lot one way or another about the political economy of aid and philanthropy. A program officer at a foundation, a community social worker, and a parent in a low-income community could all be stakeholders in an NGO but their interests are not necessarily aligned and they hold different types and amounts of power.

As a caveat, it’s worth noting that there might be a correlation between how happy different stakeholders are, even if their immediate interests are not completely aligned. For example, employees of an organization might deliver better goods or services to customers if the employees themselves are happy (I’m slipping into the “customer” mental model here).

-

You don’t really understand the “beneficiary” if you’re not one

Another document, From Constituents to Stakeholders, writes that stakeholders are “the individuals who care about an organization and consider it their own. They devote time or resources to ensure the internal development of an organization and/or its impact in the community.”

Based on this document, this model appears to work for smaller, localized organizations that provide direct services to their communities. In this case, because of the localization and shared community, the interests of the stakeholders seem to be more aligned.

But it’s unclear whether you can understand “beneficiaries” if you’re not one yourself, regardless of how “local” you are. There is a counter-example in which even hyper-localized, committed service providers didn’t really understand the beneficiaries in their community. GlobalGiving ran an experiment in Kenya to hear what “beneficiaries” cared about and then, what experts and implementers said their “beneficiaries” cared about. Only 1 in 65 experts and implementers correctly predicted the most common theme.

CONSTITUENT

Like the word “stakeholder”, “constituent” could be similarly vague. At times—typically as an adjective— it simply means being a component part of something.

But as a noun, “constituent” suggests something much more political and powerful. Here are some things from an online dictionary:

-

One who authorizes another to act as an agent: principal

(Principal: a person who has controlling authority or is in a leading position as…one who engages another to act as an agent subject to general control and instruction; specifically: the person from whom an agent’s authority derives….)

-

A member of a constituency

(Constituency: 1(a) a body of citizens entitled to elect a representative… (b) the residents in an electoral district, (c) an electoral district….)

-

An essential part: component, element

I don’t think that constituent is a perfect word. I also don’t think that there will ever be a perfect word: meaning depends on context, syntax, and how people in power choose to use the word.

But given our alternatives, constituent gets at the heart of what we want for the future of aid and philanthropy.

A beneficiary passively receives what its benefactor gives it.

A constituent authorizes what aid and philanthropy can do.

A beneficiary is not empowered to control what affects it.

A constituent can affect decision-making.

A beneficiary’s voice is not heard in aid and philanthropy.

A constituent’s voice is that around which the ecosystem is organized and oriented.

THE BABY IN A BUCKET

It is no longer being used.

I forced my colleague to proofread this piece. She raised an eyebrow.

“This is ridiculous,” Sarah said. “No where in this argument do you ask actual ‘beneficiaries’ what they want to be called.”

Touché. She’s right. A critical theorist in the making, she is asking Can the Subaltern Speak?

I give the “beneficiaries” zero agency in my argument. Do they really just passively receive? Of course not. Any ethnography in global health or development shows how actively and intelligently “beneficiaries” navigate and manipulate the complex ecosystem of projects and actors.

So forgive me in this arrogant exercise. If you are a direct “beneficiary” of a project funded through some aid agency or philanthropy, let me know what you want to be called.

Others—not necessarily “beneficiaries”—have thought much more about this issue and I would love to listen to your additional reflections on the matter. Language and meaning constantly evolve; knowledge adapts and expands, as it should.

Constituent can also be qualified – e.g. ‘primary constituents’ = those in whose name funds are raised and used.

Thanks, Andre. This is a great point. We held a LabStorm this morning which brought up how multi-layered “constituent” can be.

We discussed community-driven development projects and the tension that arises when funding goes to a “community” whose interests (defined and captured by a few) may run counter to the interests of individual constituents within the community.

What happens then and how is the donor supposed to navigate the terrain? Is primary, in this case, the community or the individual?

Great post Renee! We shared it with our online followers on https://www.facebook.com/CDACollaborative. We struggled with this terminology several times in the past and find your discussion expansive and nuanced. Best regards from CDA!

Thank you!

Wonderful to see this careful parsing of nomenclature. This is precisely the kind of analytical rigor we need to build the craft of our emerging field.

Sarah raises an important point. In our work at Keystone surveying diverse constituent groups we find that preferred self-identity varies quite a lot — patient, client, user, worker, community member, student, and many others come up depending on the context. As Renee notes, no one word is ever going to carry all the water we need!

From the perspective of building our craft — and for the same of landing defensible professional jargon — we at Keystone have also settled on constituent. Feedback, or as we call it, Constituent Voice, happens in relationships, indeed complex webs of relationships within ecosystems. Our emerging craft is about providing the signals and cultivating the attitudes and behaviors that will help us to improve these relationships. We are all “in” these relationships, and as we work “on” them, constituent may be the best term of art available.

A very interesting read on the glossary of ‘beneficiary’. We have been so used to all these words without dissecting the meaning and this piece has been a shaker with an appeal to revisit the language. It is a valid concern to ask: do we and the people we are talking about share the same glossary? Do they interpret themselves as the term suggests? It does reflect a structural unilateralism in the business of aid and philanthropy and a sense of peoples’ alienation not only in receiving the windfalls of interventions (which is questionable and requires a separate discussion altogether) but also in owning the term.

You may consider running a gallop poll but worth considering a term as simple as ‘people’- for it is all encompassing and universal or ‘community’. Although it is not unfair that every organization may choose a term to define people according to the terms of their relationships and thus we may not have a universal term but it is paramount that they understand and approve the terminology.

Thanks for the comment, Mehrunnisa. I’m glad that others are thinking about similar issues. We tried to run an online poll to find out which terms people prefer using. Unfortunately, we don’t have quite enough information to be conclusive– nor do I think we should necessarily be conclusive (as you thoughtfully point out).

We’ve also considered the terms ‘regular people’ or ‘people’ but I struggle with these as well. They seem to erase the power dynamics entirely. While we are, in fact, trying to change and improve power dynamics, I wonder if equating ‘beneficiaries’ with ‘funders/implementer’ (“we are all people”) actually does a disservice by almost hiding the fact that that there is difference between the two categories.

In the violent racial climate of the United States, there are parties that say “Black Lives Matter”; others say “All Lives Matter.” Judith Butler writes, “When some people rejoin with “All Lives Matter” they misunderstand the problem, but not because their message is untrue. It is true that all lives matter, but it is equally true that not all lives are understood to matter which is precisely why it is most important to name the lives that have not mattered, and are struggling to matter in the way they deserve.”

Words can obviously be very powerful, and how we refer to people can influence our thinking about those people and our actions towards them. In that regard, I think this post does a good job at delving into the semantics of each term. It is important to remember, however, simply selecting the term that most accurately describes the state that we want to see or the one that we have convinced ourselves is the reality, does not actually change things. And in fact, can make things worse. If all of a sudden development actors start calling people ‘constituents’ without changing how development is done it is problematic for many reasons.

In my opinion, the development world does not currently treat people as if they are constituents, so calling them so would only mask the reality of a flawed system while making those actors who we tend to refer to as ‘implementers’ feel better about themselves for working in such a wonderful industry that fully values those people we are supposed to be serving. Let’s reform our language, but also reform how we actually treat people. The latter is a whole lot more difficult, but without it any changes to the terms we use to describe things are, to paraphrase Sarah Palin, just putting lipstick on a pig.

In every case, I first try using the word “people” and only when that is too vague, I switch to “citizen” then “constituent” and sometimes “beneficiary” when I only want to describe people directly affected by a specific project.

What this word should remove from our mental picture are institutions. People are the only stakeholders I care about, and a person who lobbies for an institution’s interest should have a back seat over people with no organized voice.

In my previous organization, we called them “primary actors” since these people are not passive recipients of aid. They are the ‘primary actors’ and they were at the heart of our work.