September 22, 2015

Photo Credit: GlobalGiving

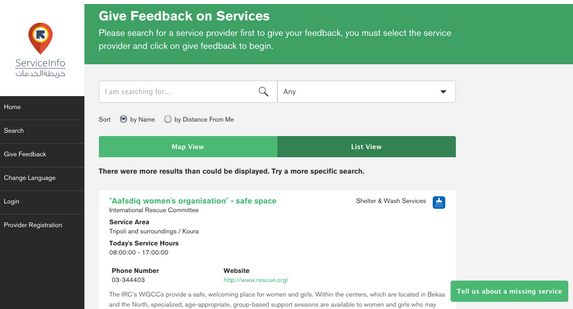

Earlier this year, the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a leading humanitarian organization, launched a feedback tool IRC Service Info for the over 1 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon. According to IRC, “Service Info is designed to be used by service providers to coordinate and increase responsiveness, and by service users to find and provide feedback on the services relevant to them.”

At first glance, it looked as though IRC Service Info would function a lot like Yelp, a commercial website that allows users to comment and leave feedback on small businesses—restaurants, hair salons, cafes— and now, even on US federal government agencies.

People can use IRC Service Info using a computer or mobile device. The website is in English, French, and Arabic. For individuals without online access or who prefer using a phone, they can also call to provide feedback to particular services.

This could be an exciting platform to increase the role of constituent feedback in humanitarian aid.

After spending some time on the website (toggling between the different languages), I noticed something that made it very different from Yelp. I didn’t see any user reviews despite this being an explicit goal of the project.

So, I contacted IRC and they responded quickly and with great “customer” service.

IRC told me that all feedback is collected and goes through a vetting process. Then the vetted feedback gets disseminated to service providers anonymously.

You can see the “feedback report” only if you are a service provider, not as a general member of the public.

If I were a user of IRC Service Info, I think I would want to see what other people have to say.

Yelp, while not perfect and definitely a curator of user posts, is useful because I can see what others have said about a business. Did others enjoy their meal at that restaurant? Perhaps the Syrian refugee would ask: did other women get treated well at that health clinic?

The public nature of posting on Yelp is also important to me because what I say as a consumer matters more when many have access to my opinion. When information becomes public it can pose a reputational and commercial risk to businesses. In that way, it may put more pressure on them to respond.

The IRC representative thoughtfully raised the following point:

-

- “The audiences are quite different. It wouldn’t be fair to allow anonymous feedback on service providers, which is why Yelp requires a user account to be created before one can post feedback.

Since our target audience comprises refugees and perhaps other vulnerable populations, we didn’t think this was the way to go, at least not for the pilot phase. Also, requiring a user to create an account before submitting feedback introduces more ‘friction’ into the process, and we are worried that some users wouldn’t bother.”

The difference in audiences is a great point and something I didn’t think would be a huge factor. I hadn’t thought about vulnerability, protection, and anonymity because I don’t work directly with refugees.

I’m like the well-meaning app developer in the Silicon Valley who shouldn’t develop a tool for a population I don’t understand.

I don’t realize that maybe uncensored public comments on Service Info can inflame heinous sectarian violence. That maybe service providers fear for their lives in ways that service providers on Yelp don’t.

I still question IRC’s concern about the “fairness” of allowing anonymous feedback on service providers. Other platforms allow consumers to give feedback without a user account, without ever revealing an identity. On Yelp and other account-based services, users don’t have to use their real names. Unless people are maliciously and unreasonably attacking the service provider, it’s generally not a problem. Yelp does remove occasional inappropriate content and sets guidelines for its community, but generally the community can govern itself.

I also question how engaging a “cold” website is—one that doesn’t show lots of user activity to the public. IRC is concerned that having to create user accounts introduces an additional step—a hassle factor—that might prevent people from using the site. This is a good behavioral insight. But here’s another: people need social affirmation; they behave based on what they perceive to be the social norm. So having a website without showing other user comments can actually deter people from posting. They might think they’re the only one doing so.

So, I’m still left wondering:

Does feedback have to be made public in order to be useful? And what are the tradeoffs in a humanitarian context with vulnerable populations?

Take for example a related online platform for Syrian (and other) refugees: Facebook. As thousands migrate to Europe, open Facebook pages help to guide them. Traffickers sponsor and manage some of these pages. But many pages are created by migrants themselves to give advice on how to smuggle yourself for free.

The pages function as information boards with crowd-sourced content. They have comments, questions, feedback, and “likes” from real migrants. Everyone using Facebook has a user account. Hundreds of thousands are using this platform because there’s something reassuring about learning from what someone else has experienced.