Photo Credit: World Bank

Author: Renee Ho

The World Bank is a bank– at its core it lends money to developing countries for capital programs. It has tried–to its credit–to be much more than this.

In 1998/1999, it published its flagship World Development Report Knowledge for Development. The report “acknowledges that knowledge, not capital, is the key to sustained economic growth and improvements in human well-being.” It conflates knowledge with technology and information, suggesting that knowledge is like a commodity that can be easily packaged and consumed.

Reports aren’t knowledge. This is what Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline, explained at the World Bank today, sixteen years later.

The room filled with nervous chuckles. There was tacit knowledge that Senge was on to something.

Soon after joining the World Bank, I was socialized to casually use the phrase “knowledge product” as though it meant something. And it did– tacitly, it meant I was working on a glossy-papered publication that likely no one would read.

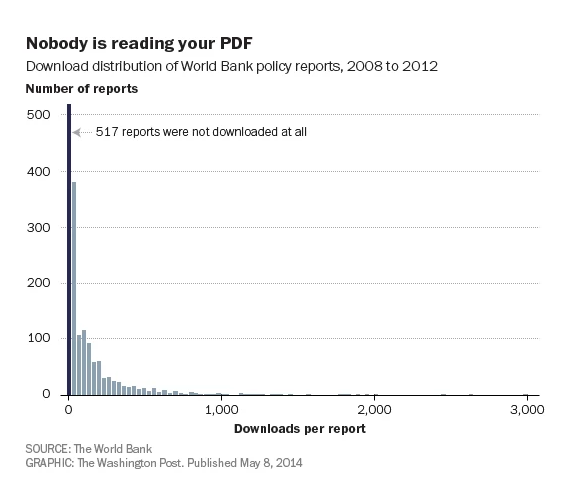

In 2014, in a strangely transparent meta-analytical exercise, the World Bank issued a report called, Which World Bank Reports are Widely Read? It found that 517 reports were not downloaded at all (between 2008 to 2012).

If reports aren’t knowledge, what is?

According to Senge, knowledge is the capacity for effective action.

Reports, on the other hand, might capture information or insight. You know, best practices and lessons-learned. These things, in themselves, do not constitute capacity for effective action.

There is no manual that we can read to learn these things, no class we can take. Sure, there might be some best practices or lessons-learned we can read in a report but we will not fundamentally succeed in this way.

Similarly, schooling for a child is often less about learning and more about socialization. Attending a training seminar for a bank employee is the same thing: what you learn is not effective action but social norms and incentives. What makes your boss happy?

So if knowledge requires learning, and learning requires failure, the question for the World Bank (among others) might be:

How do we promote a culture that encourages learning through failure?

According to a recent survey, the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) found that only 1/3 of World Bank staff feel that they can openly talk about problems they face regarding their lending practices.

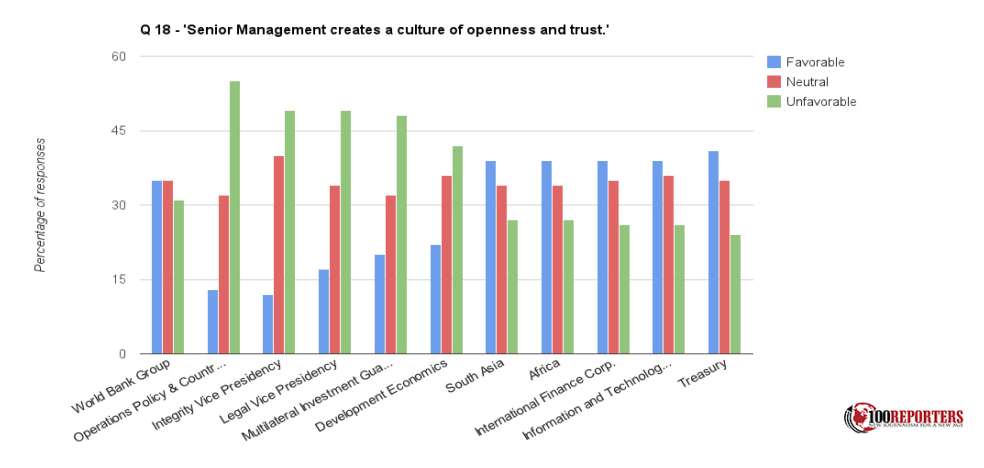

Last year, in a much more extensive survey, a significant percentage of employees feel that senior management does not create a culture of openness and trust.

Senge emphasizes the need to create a safe environment for failure. We need to be able to get feedback and tumble a little before properly standing on our feet.

Project restructuring should be perceived as a positive social norm, not a failure. IEG should not downgrade its evaluation of a project because it has to be modified. Renaming it wouldn’t hurt: restructuring suggests that the project designer didn’t structure it correctly the first time around (and people at the bank like structure). On the other hand, adaptive management sounds like the project is resilient, responsive, and under control– there is no failure, just learning.

In any organization, knowledge– the capacity for effective action– should be the measure of one’s worth. This should be rewarded, prized, and held high by the President of the World Bank.

I left the Senge talk and opened my email. A letter from Jim Kim.

Dear colleagues,

Today, as fiscal year 2015 comes to an end, let me share with you some of our accomplishments over the last year. There is no doubt that across the entire World Bank Group our excellent teams have performed exceptionally well.

During the last fiscal year, the World Bank Group’s financing for fiscal year 2015 will be about $65 billion, compared to $53.4 billion in fiscal year 2013 – roughly a 22 percent increase in two years. In particular, I’d like to single out two achievements: IBRD’s lending will be about $23.5 billion – a record for a non-crisis year; and IDA funding for the first of a three-year period will be about $19 billion – again, a record for a first year of IDA funding….In his benevolence, Kim gives all staff July 6th as a holiday “in appreciation of [their] work.”

This memo sends a clear signal of what senior management expects for staff across the globe: the World Bank measures its worth by how much money it pushes through the door; staff, in turn, will be rewarded accordingly.

And so, with a self-congratulatory flourish, the World Bank pats itself on the back and closes fiscal year 2015. Not with a bang, but a whimper.

About the Author:

Renee Ho is Insight Curator at Feedback Labs. She has worked at the World Bank, ideas42, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She has a BA in Political Science from UC Berkeley and an MPA from the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University.

interesting article. I agree that reports are not a knowledge product. however, until we are able to define this, in a more tangible, measurable way, documents and reports are always will go into that bin. How do we inventively capture the knowledge capital lend by a project through all the financing done?

the only way, until the bank is able to interpret dollars for effort, thus, amount of learning invested, reports on increased dollar expenditure will always reflect knowledge. the question is how do we know that you have mastered riding a bicycle? Once that is done, the tutor is out of a job….

Thanks so much for your thoughtful feedback!

I think the development industry should generally avoid thinking of “knowledge” as a noun and a commodity. One way I am thinking about it: there is a difference between knowledge and learning. One is static, the other dynamic. We should try to focus more on learning (the dynamic one) because that is what gets results, not necessarily knowledge (the static one). In that sense, we can worry less about “knowledge capture” and more about learning.

You bring up a good point– how do we know when we’ve mastered riding the bicycle? I think there are a few potential indicators– the desired outcomes/impacts are achieved and/or we get positive (and honest) beneficiary/constituent feedback. Some exciting early literature that says there can be a correlation between outcomes and feedback.