Feedback is one of those principles that has everyone nodding along. “Yes, yes, we need more of that.” It’s hard to argue against feedback on its own merits.

However, we still face hurdles in getting better feedback incorporated into development and aid work. These hurdles rest on a combination of conflicting principles (such as cost-cutting), narrower interests (such as ego or organizational reputation), and simple lack of knowledge or understanding. Facing any of those hurdles, it helps to recognize that feedback is not a monolithic or simple thing. It can take many forms depending on the context and goals.

What follows is an attempt to disaggregate the concept of “feedback”—broadly defined as a full process loop (both the intake of information as well as the output response it provokes) by which an organization adapts in its efforts to serve a community. The resulting framework could be variously applied to any type of organization, business, government agency, etc., though we’ll mostly focus on the aid and development sector.

The point of disaggregation is to show how the various components can align (or not) to ensure that feedback loops contribute to broader goals.

Intake: Channel and information

The first two components of feedback are the channel and the information. These constitute the narrow, unidirectional meaning of the term “feedback” that’s used in most management situations (e.g. “Hey, can I give you some feedback on that design?”) or when thinking about customer feedback.

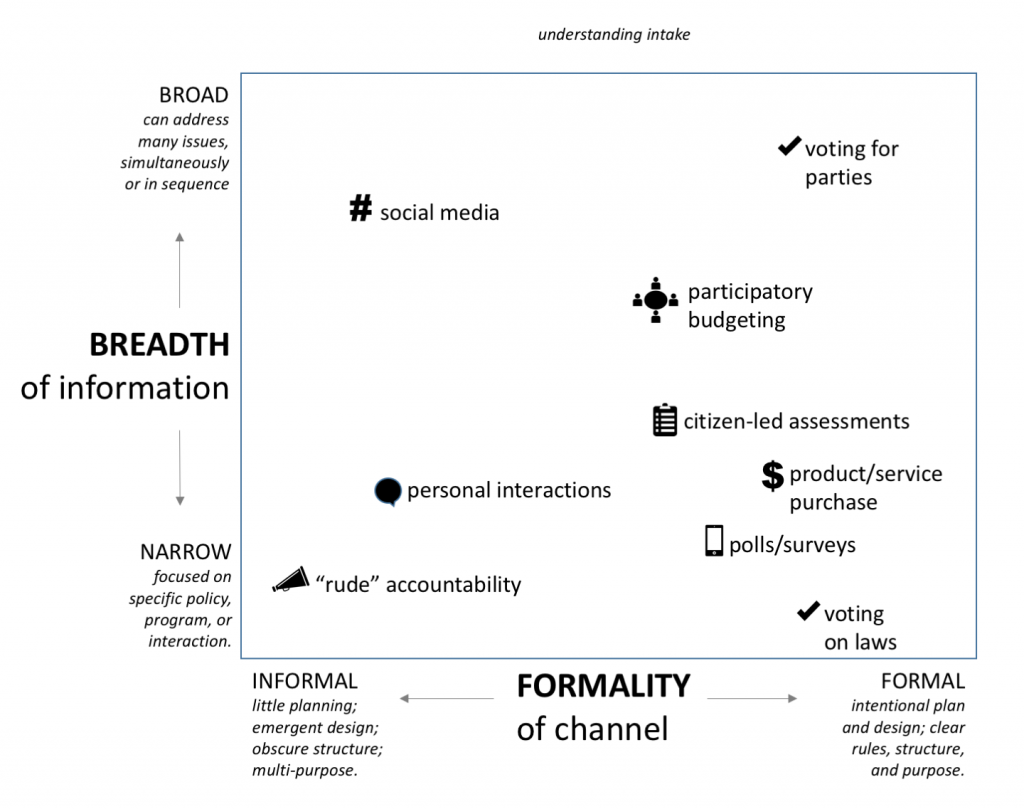

Channels—the means through which feedback intake is received—can be formal and designed for a specific purpose, or less formal and arising with less planning. Voting and surveys both sit on the formal end; social media comments and personal interactions are more informal.

Likewise, information—the content of the feedback intake—can be narrow or broad: voting on a law carries a very narrow judgment, as does a survey; voting on parties or participatory budgeting processes cover broader ranges of issues.

This arrangement should help us think a bit more creatively about the types of channels and information through which feedback flows. The less formal methods—such as the “rude” accountability that people use in the face of poor pubic services, or personal interactions between constituents and decisionmakers—would rarely show up in an M&E, learning, or feedback plan. Yet these are critical types of feedback intake in many situations.

Output: Motivation, lever, and action

The other half of the loop is the change that occurs in response to the intake: the motivational component that compels a change, and the response lever for change through which an action occurs.

This loop applies to the physical as well as human realms. That screeching noise you hear when a microphone gets too close to a speaker is called audio feedback: the microphone picks up the noise from the speaker, feeds it through an amplifier, out the speaker, back to the microphone again, and the loop continues.

When you hold a microphone in front of its speaker, you’re also part of a different feedback loop:

- Channel: Loud, screeching noise.

- Information: The microphone is too close to the speaker.

- Motivation: That noise is really annoying and you’d like it to stop.

- Lever: You’re holding the microphone.

- Feedback action: Move the microphone.

This framework parallels the loops of Feedback Labs’ own model: design, collect, analyze, dialogue, course correct. However, it’s worth underlining the motivation and lever components.

In social change and development settings, we generally take ourselves and our organizations to be well intentioned actors seeking the greatest good. We often imagine that if only we got the feedback information into our organization, then the right actions would result.

This assumes two things: first, that we will be intrinsically motivated (by some combination of personal values, organizational culture, or mission) to respond to the information gathered, without an external force pushing us; second, that we have (or will find) the levers to respond. These assumptions allow us to focus more on ensuring that there are channels: surveys, focus groups, social media, and more.

Do these assumptions hold? Not always. Organizational constraints and business considerations often trump the motivational elements and prevent us from finding new levers. To make that concrete: We may be hearing from our constituents that the health programming needs a nutritional component, but our grant is written too narrowly and we can’t bring in other funding.

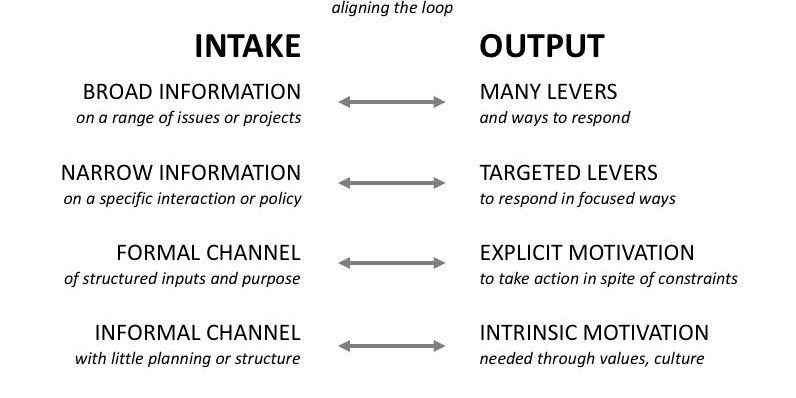

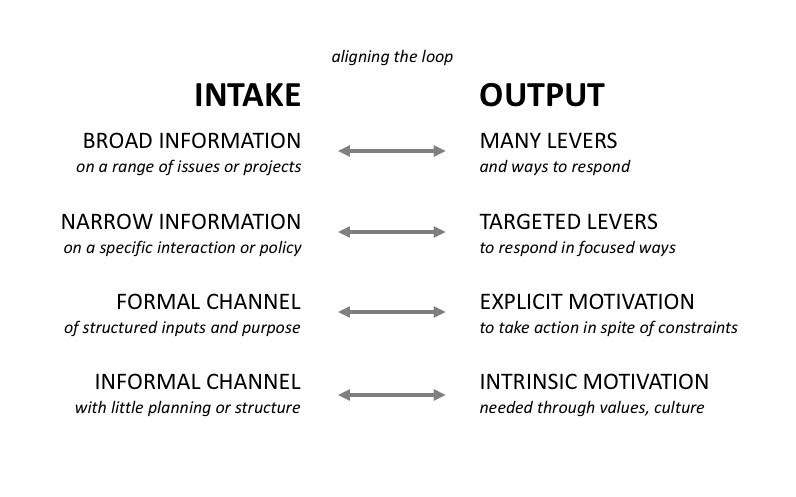

Aligning the loop

Overcoming these hurdles is easiest when the action in response aligns with the other components of the loop. Different types of intake fit better with different types of output. At a general level: broader information on a range of issues coming into the loop (the top half of the diagram above) requires a broader ability to respond and shift direction—hence, a wide variety of levers, programming, policies, and more.

For example, think about an election as a feedback mechanism that matches broad information with many levers: The government receives information from the voters in the form of votes, and then has an entire policymaking and bureaucratic apparatus to take actions. In contrast, a narrower set of information coming into the loop only demands a narrow set of levers for response.

Likewise, looking at the other axes, the formality of intake channels is correlated to the explicitness of output motivation. Market forces (the purchase of a product or service) are the prime example of highly formal channels that explicitly motivate responses.

This framework suggests a way to diagnose organizational hurdles in effectively incorporating feedback loops. If you have informal intake channels but lack the intrinsic motivation to respond, you likely need to either build intrinsic motivation (for example, through a focus on organizational culture) or formalize the intake in a way that builds explicit motivation.

Similarly, you could design backwards from the outputs to the intakes. If you know that your program has and needs diverse response levers to accomplish its goals, then you should look for broad information intakes that you can sift through for actionable insights.

Whether with this framework or another, we need to disaggregate the concept of feedback in order to operationalize it. Everyone accepts this as a value; we need to find better ways to do it in practice.

About the author:

Dave Algoso (@dalgoso) is a manager, facilitator, and writer in the international development and social impact sectors. His work experience includes a variety of research and implementation projects related to governance, social accountability, civil society, and peace-building. He also writes regularly for his own blog, Praxis.

Dave Algoso (@dalgoso) is a manager, facilitator, and writer in the international development and social impact sectors. His work experience includes a variety of research and implementation projects related to governance, social accountability, civil society, and peace-building. He also writes regularly for his own blog, Praxis.